Everyone is overreacting to the Mexican president's attack on electoral institutions ... and that's a good thing

Mexican democracy is not in danger, but that’s because all these people are acting like it is

The Mexican Supreme Court just put a temporary injunction on President López Obrador’s (henceforth AMLO) attempt to weaken the National Electoral Institute (INE). Otherwise sober observers awaited the decision with an almost existential dread:

Almost one month ago, on February 26th, the streets of Mexico City filled up with mass protests when the new law passed Congress. The protestors—and many academics—see the reform as a power grab, one step on the way to recreating the old PRI dictatorship, only this time under Morena, the party AMLO created when he failed to get control of the old Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD).

TLDR: everyone is wrong. They are not wrong that AMLO wants to destroy Mexican democracy! But they are wrong that he can. Even if they’re upheld, AMLO’s reforms won’t destroy Mexican democracy. They’ll barely even weaken it. You might fear the beginning of a slippery slope but that slope won’t slip. And the reason that the slope won’t slip is because all these people are all worked up over it. If people were just letting this minor pissant reform pass by, then I would be terrified. But they aren’t, and I ain’t. Viva México!1

This post proceeds as follows. Section 1 recounts what INE does and how it works. Section 2 talks about why and how INE was created. Section 3 describes AMLO’s attack on the institution. Section 4 explains why I am not worried about a return to dictatorship.

(1) What is INE?

What is the Instituto Nacional Electoral? Well, it’s the constitutional body that runs and regulates elections. It was created in 1990 to oversee federal elections, separated from the executive branch in 1996, and placed in charge of state and local elections in 2014. (That was when its name changed from “Instituto Federal Electoral” to “Instituto Nacional Electoral.”) Under article 41 (mostly) of the Constitution, INE organizes elections, makes sure that the candidates stick to the rules, and punishes violations. (There’s also a separate Electoral Court, which is part of the judiciary.) Members of its governing council serve nine-years terms and need a 2/3rds vote from Congress. Its personnel come up through a track separate from the rest of the civil service.

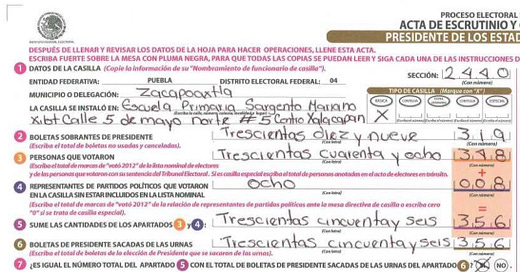

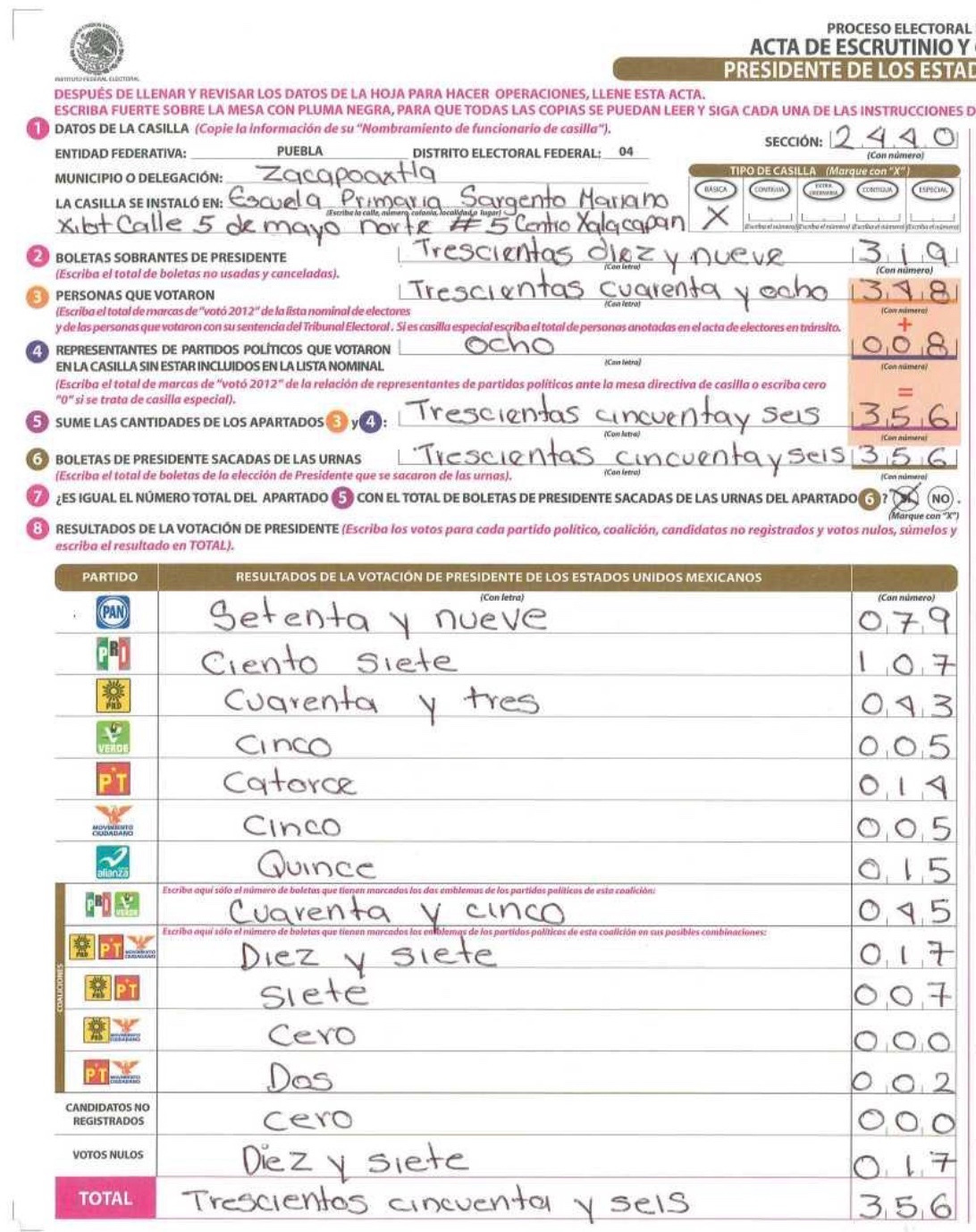

So far, so boring, but there is one fun extra bit to the system: Mexico selects poll workers by lottery! You can turn it down, just like jury duty in most common-law countries. But it’s those citizens, over a million of ‘em at each election, who watch polls and count ballots alongside the INE professionals. (My friend and former student, Enrique Seira, has looked into how this system works. Not terribly!)

(2) Mexico Before INE

Mexico was a dictatorship before 1996. Period. The country’s first moderately free election happened in 1994. (I do indeed mean “first in history,” not merely “first since the Revolution.”) Its first truly free election was the 1997 midterm. Its first completely free general election happened in 2000. There used to be a whole cottage industry of academics who used weasel-phrases like “single party dominant regime” to pretend that it was something other than what it was: a dictatorship. The Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) ran the show.

Sometimes you had election drama, but not of the good sort. Frex, General Miguel Henríquez decided to contest the 1952 election against the PRI. Well. The PRI arrested opposition candidates for a crime called “disolución social.” It broke up opposition rallies with gunfire—on election day alone, police killed seven people. It openly stuffed ballots and won 74 percent of the vote. (They’d go back above 90% in the 1958 “election.”) Henríquez refused to concede … until the PRI found a way to buy off him and his supporters.

Now, the PRI was a “soft” dictatorship. (Russians would call it “vegetarian.”) It tolerated open dissent. It allowed opposition parties to exist. Hell, it financed opposition parties in order to give the appearance of democracy. It preferred to purchase or co-opt opponents rather than kill or imprison them. It held “elections.” The vote theft was kept to a tolerable minimum. People, it wasn’t the Bolivarian Republic, let alone Communist Cuba.

But the wheels nonetheless came off the bus in the 1980s, when the economy collapsed. Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, the son of President Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-40) broke with the PRI and ran for the presidency in 1988. The conservative National Action Party (PAN) backed the left-wing Cárdenas. It looked like 1952 all over again … and turned out to be worse than that.

When federal electoral officials began counting ballots on the evening of July 6, 1988, early returns placed Cárdenas firmly in the lead. Vote tallies arriving later from rural districts and other parts of the country favored the PRI, but officials panicked, and claimed that a computer failure prevented them from releasing preliminary results. The PRI, in violation of a multiparty agreement reached before the elections, claimed victory for PRI candidate Carlos Salinas.

When the Federal Electoral Commission announced official results a week later, it declared PRI candidate Salinas the winner (with a bare majority of 51.7 percent of the total valid vote, compared with 31.1 percent for Cárdenas and 16.8 percent for PAN candidate Manuel Clouthier) in what was at the time widely regarded as the most fraudulent election in modern Mexican history.2 And what is now regarded as a simple blatant fraud. The government didn’t steal the election so much as simply announce that it had won and hope for the best.

But the PRI leadership didn’t believe simply announcing a victory would be enough. The opposition was too broad—and too elite. Mexican governments could go all 1952 and shoot peasants and workers. It could even go all 1968 and shoot lower-middle-class college students. But it couldn’t shoot rich Regiomontano industrialists and angry suburban voters in Hermosillo and members of old elite Revolutionary families in Mexico City. Not all at one. Something else needed to be done.

“Something else” turned out to be an agreement with the conservative PAN. If the PAN would vote in the Chamber of Deputies to certify Salinas’ election—and let the government burn the ballots afterwards—then the PRI would respect the PAN’s victories in gubernatorial, mayoral, and municipal council elections and pass laws letting the PAN compete in future elections.3

The ballots got burned. And a new electoral law got passed.

Empersay IFE

The new electoral law did two things. First, it created a complicated set of electoral procedures that the PRI hoped would let it keep winning legislative majorities without the need to steal elections.4 Second, it created the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE) to oversee federal elections. (State elections were still a free-for-all.)

Now, IFE still wasn’t be a fully independent body. The Interior Secretary chaired the damn thing, after all. But the other 10 members of the governing council would consist of four legislators and six independents picked by the political parties. The upshot of that was that in 1994 the opposition controlled 8 of the 11 seats on the governing council. Moreover, the legislation allowed for independent and international election monitoring and reviews of the vote counts.

In general, the 1994 election was pretty clean—Ernesto Zedillo won by a large margin, only a little ahead of the opinion polls. But “pretty clean” isn’t clean and IFE proved its mettle by overturning a bunch of results, including the mayor of Monterrey and two congressional seats in Jalisco and Michoacán. More importantly, however, the opposition mobilized some 400 groups into the “Civic Alliance,” which ultimately mobilized 40,000 citizens to watch the polls.

This was the context in which President Ernesto Zedillo pushed the 1996 electoral reform that made IFE autonomous and altered the Congressional rules to remove the PRI’s advantage.5 The result was a free and fair midterm election in 1997 and a free and fair presidential election in 2000. And again in 2006 and and 2012 and 2018. Plus the midterms and a whole lot of state and local elections from 2014 onwards.

AMLO and IFE

In 2006, AMLO faced Felipe Calderón in the general election. When asked if he would accept the result, he waffled, exactly as Donald Trump would waffle in 2016. After he lost in a squeaker, he claimed fraud. Fights broke out in Chamber of Deputies as his Congressional supporters tried to block his opponent’s inauguration. He led mass rallies in protest. He then imitated Francisco Madero in 1910 and himself proclaimed the legitimate president, complete with his own inaugural ceremony in the Zócalo. None of this indicated a man particularly enamored of democratic norms. He considered the then-IFE part of the conspiracy against him.

The same movie repeated itself in 2012, even though he lost that election by a commanding margin. There was no evidence of fraud. There was some evidence of illegal vote-buying, but the margin was too large for it to explain the results. That time, however, he didn’t establish a parallel administration. There were pretty serious protests through the end of the year, but AMLO wasn’t organizing them directly.

Nevertheless, he remained bitter at INE.

(3) AMLO’s attack on INE

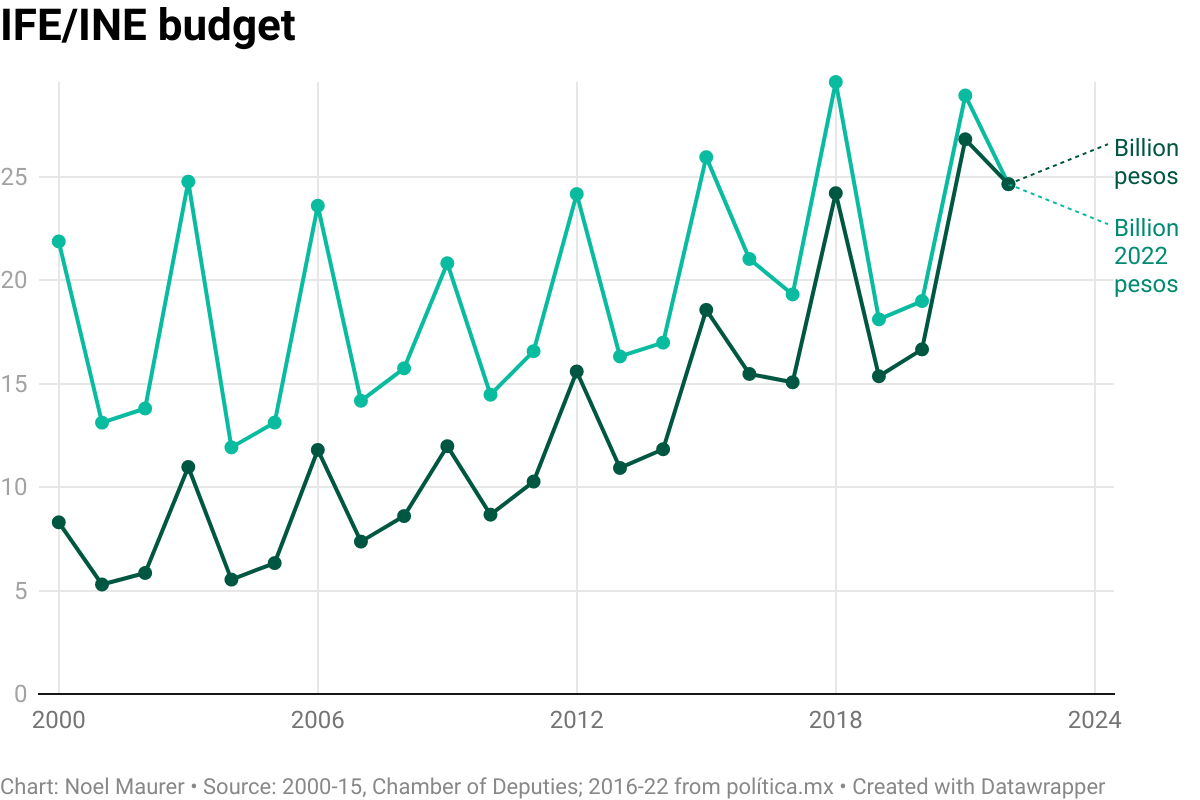

Allow me to concede one point to AMLO: in comparative terms, INE is expensive. In per voter terms, the administrative costs of Mexican elections are the highest in Latin America. Around 2004, Mexican elections cost about US$5.90 per voter to run, whereas Chilean elections cost $1.20, Costa Rican votes require $1.80, and Brazilian polls cost $2.30. (See also here.)

That said, in the latest midterm election (2021), INE cost only 0.4% of the federal budget.

AMLO tried to change the Constitution to neuter INE, but he failed. So he went with “Plan B,” a simple law which would do a lot of things, but mainly cut the budget by 3.5 billion pesos and lay off about 85% (!!!) of the Instituto’s full-time personnel.6 If you really want to read all the details, you can find it here. Now member, most election monitors are essentially draftees, so the reduction isn’t quite as bad as it seems, but it’s bad.

If it survives Supreme Court review, this will clearly hurt INE’s ability to do its job.

(4) So why am I so sanguine?

Two reasons. Well, maybe only one.

At the end of the day, countries have free elections because their populations demand them. There are conditions under which no government can resist those demands. If the pro-democratic forces include key support groups, then the government will have to allow free elections. If the pro-democratic forces are large enough, then the government will have to allow free elections. If the anti-democratic forces lose faith in what they are doing, then the government will have to allow free elections.

All three of these factors held in Mexico in the decade after 1988. It is true that Ernesto Zedillo was a genuine democrat—he should be viewed as a hero of Mexico—but the PRI didn’t give up control because Zedillo enjoyed unusual authority or astonishing powers of persuasion. It gave up control because it had to. Trying to hold onto power would have made Mexico ungovernable and threatened the livelihoods of the politicians who controlled the PRI machine.

Today AMLO can weaken INE, and that is a bad thing, but abolishing INE will not suddenly allow him to steal elections. If AMLO or his party, Morena, tried to roll out PRI-tactics circa 1976 they would face a united opposition, watch swing voters peel away, see giant mass demonstrations, confront an extremely vocal United States, ignite Congressional firestorms, lose party discipline, and almost certainly have to back down.

In other words, if the PRI couldn’t maintain a dictatorship in 1988, then AMLO can’t create one in 2024. Or 2030. Or 2036, assuming we’re not all under the control of GPT-11 by then.

If Mexico’s past doesn’t reassure you, then look south to Argentina. Unlike Venezuela and Nicaragua (but like Mexico) the opposition there remained active and engaged throughout the Kirchner years. Cristina could not steal elections nor create a dictatorship. Argentina has no INE, and its elections are messy, but they are generally free and fair.

Even if AMLO managed to eviscerate INE, we wouldn’t be back to the 1980s. In fact, if anything the move would backfire, especially once AMLO himself isn’t on the ballot. By mobilizing opposition, it will have the effect of slowing down his slow attack on democratic institutions.

I would have been worried if his moves generated only weak responses—but they did not. Even if the “Plan B” reforms survive the Supreme Court, AMLO has scored an own goal.

Sure, in theory AMLO could construct a political machine that would remove people’s livelihoods and punish dissent. It happened in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela; it happened in the Russian Federation. But in practice, the Mexican state faces too much organized and resourceful opposition. For example, AMLO has had it in for my old employer, ITAM, a major Mexican university. And AMLO has hurt ITAM, not least by wrecking any employment opportunities its graduates may have had within the federal bureaucracy. But ITAM soldiers on, because it has powerful private support and widespread popular legitimacy.

For former President Miguel de la Madrid’s own remarkably inadequate explanation of the disputed vote count, see De la Madrid (2004), pp. 814–25, 834. Salinas’s defense appears in Salinas (2002), pp. 949–65. For an analysis suggesting that Cárdenas won more votes than Salinas, see Castañeda (1999), pp. 327–8. The elections for the lower house of Congress were equally shocking: the obviously fraudulent vote totals showed PRI candidates earning only 50.4 percent of total votes cast, the lowest proportion in the history of the party. PRI candidates for federal deputy positions had garnered 86 percent in 1964, 85 percent in 1976, and 69 percent in 1982.

Yes, there are definite shades here of what the Trump Administration hoped to do in 2020-21. Well, maybe not just shades. Statues? Giant concrete representations? Anyway, the Trump Administration had worse politicos than the PRI of 1988 and was operating in a completely different historical context. But you’re not wrong in hearing the rhyme.

The constitutional changes were pretty clever. In the lower house, the new rules stated that any party which won more single-member districts than any other party and obtained at least 35 percent of the total vote share would get a majority of the lower house. In 1993, the PRI agreed to dump that clause, but they replaced it with one that made cross-party coalitions impossible: any two parties that wanted to run a joint presidential candidate would also have to run joint candidates in every other election and publish a single combined platform. Nobody would be allowed to repeat Cárdenas’s 1988 run. Basically, the PRI had realized that it couldn’t get away with blatant fraud anymore and was rejiggering the Constitution to suit.

The ‘96 constitutional amendments stipulated that no party’s share of lower house seats could exceed its share of the national popular vote by more than eight percentage points. In the Senate, it gave two senators per state to the plurality winner, with one seat to the runner-up, for a total of 96 seats. Then an additional 32 seats would be allocated via proportional representation

Much of the budget consists of public campaign funding.